Facts Related to Flukes

Liver fluke disease in cattle, sheep, llamas, and other ruminants recently has become more prevalent in the U.S. and many other countries due to increased interstate and overseas transport of animals and alterations of the environment, such as the creation of lakes, ponds, and irrigation systems which support the intermediate host snail. Infection can result in profit loss due to reduced meat and milk production, lower fertility, condemnation of livers, and death.

Liver fluke infections occur mainly between June and November in areas with freezing winter temperatures. The best time to treat for liver flukes is November in the northern states and December in the southern states after cattle have been taken off summer pasture.

The pre-patent period is 7 to 8 weeks. Encysted metacercariae will survive freezing winter temperatures and can become infective in the spring. Eggs are produced and shed throughout the winter but do not develop until the temperatures get above 50º F. Infected cattle develop a slight immunity but not enough to give complete protection from subsequent exposures.

Lung flukes are acquired by cats, dogs, raccoons, and other animals through the ingestion of crayfish and crabs.

The reservoir host for Paragonimus kellicotti, which infects dogs, cats, and other small animals, is the mink. One study was done in Ohio in 1964. In that, it was found that 34% of wild mink were infected. The first intermediate host is the snail, and the second is the crayfish. The crayfish is an abundant food source in the southeast United States, which leads to a serious problem with lung flukes in the animals which eat the scraps or culls.

A similar lung fluke, Paragonimus westermanii, which has a more extensive range of hosts, including man, is spreading world-wide with the highest incidence in Asia. The first intermediate host for this fluke is the snail, and the second is the crab and crayfish.

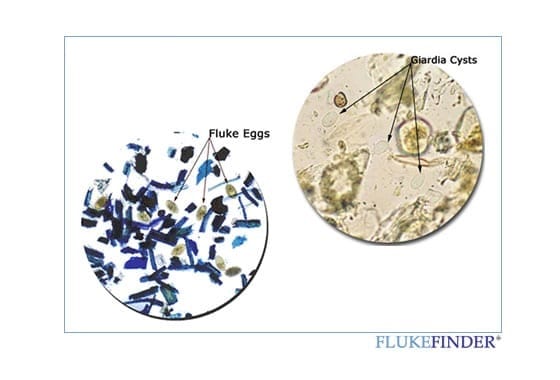

Eggs of both types of lung flukes are captured from fecal samples by the FLUKEFINDER® using the same process as for liver flukes.